This is an illustrated transcript of Medieval Christmas, a feature I wrote for BBC Radio 3 Nightwaves. Downloadable as a BBC podcast here or here.

It’s cold outside. Inside a large fire burns brightly filling the room with intense warmth. The occupants inhale the scent of decorative evergreens, drink sweet wine, and tuck into a hearty meal. Later they play games, listen to music, dance, sing carols, and exchange seasonal gifts and greetings. For many of us, this scene feels like a snapshot of the celebrations to come on the 25th, but it’s not. It’s Christmas in the Middle Ages.

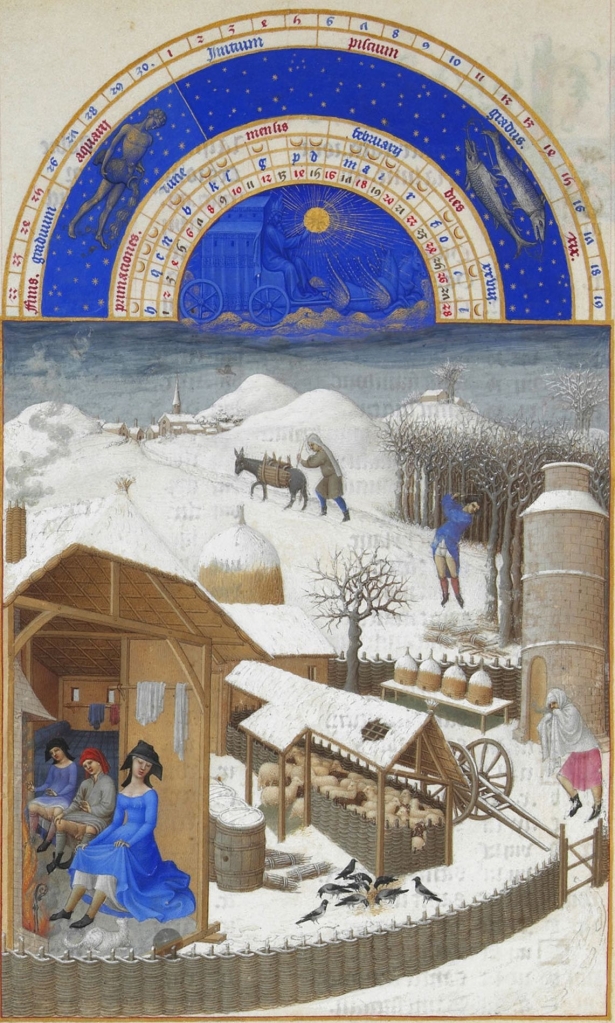

Calendar page for February in British Library MS Additional 24098 ‘The Golf Book (Sixteenth Century)’.

If we could go back in time just over six hundred years, the festive season would be both familiar and strange. Then, just like now, Christmas preparations began weeks in advance, but what people busied themselves with before celebrating the birth of Christ was very different. Advent was a time for fasting, slaughtering and salting animals that wouldn’t survive winter, and participating in irreverent customs like the Boy Bishop ceremonies held on the Feast of St Nicholas, when children would be elected to preside over all the tasks assigned to real bishops, except mass. Effectively in control of the bishopric, the boy bishop and his attendants would travel throughout the diocese offering blessings, declaring holidays, singing, and dispensing treats. In return they’d receive gifts, hospitality and entertainments.

Christmas preparations on a calendar page for December in ‘The Golf Book’. British Library MS Additional 24098.

Rituals like this, and the election of Lords of Misrule to oversee the festivities in noble households, were part of the popular carnival entertainments associated with the season. Temporarily letting the underdog have his day, by throwing aside the normal order of things in a controlled period of misrule, was incredibly popular and made the peasants more accepting of the feudal system that restrained them for the rest of the year.

Christmas Day marked the start of an indulgent period of at least 12 days of feasting, though truly extravagant festivities in royal and noble households might extend for 40 days beyond Christmas to Candlemas in early February. The lengthy nature of the celebrations was due to several factors, the most practical being the difficulty of travelling in the winter season, the abundance of fresh meat, and the fact that there was little agricultural work in the dark winter days.

And it wasn’t just the length of the celebrations that were staggering by modern standards, but the volume of guests that were catered for by the wealthy. In the 1390s Richard II hosted the most lavish banquets, employing 300 cooks and servants to feed 10,000 people with 28 oxen, 300 sheep and innumerable fowl served up each day.

The romance of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, vividly evokes the spectacle of a royal banquet, telling us that each course was brought out to ‘the blaring of trumpets’, ‘kettledrums’, and ‘pipes’, as each couple shared ‘twelve dishes, good beer and bright wine’. Food would include wild boar, fowl, pies, stews, bread, cheeses, puddings, and large rectangular shaped pastries filled with minced meats like pork, eggs, fruit, spices, and fat, the precursor of our mince pies. Before and after the hubbub and splendour of the banquet, raucous revels like tournaments, dancing, and playing games, would occupy guests.

Celebrations in noble and gentry households were much smaller in scale, but just as impressive. A letter from Margaret Paston to her husband John, written on 24 December 1459, outlines festive activities that their neighbour Lady Morley had banned the previous year when mourning the loss of her husband: ‘there were no disguisings [masques],’ she said, ‘ nor harping, nor luting, nor singing, nor no loud pastimes’ only ‘playing at the tables, and chess, and cards’ was allowed.

At the lowest end of the social spectrum, peasants celebrated with dancing, singing, dice games, and mummings, where participants would don masks and visit local households singing and asking for Christmas charity. Christmas day was a quarter day, which, rather miserably, meant that peasants had to pay rent to their lord, but they received gifts of food, ale, clothing, and firewood in return, and this was one of the rare times that they would get to eat meat. They too celebrated for the duration of the twelve days of Christmas, returning to work after the feast of the Epiphany on 6 January.

It’s through the poorest people that we see the true essence of Christmas in the Middle Ages: a spirit that speaks to our own age of austerity. For them, Christmas was about simple inexpensive pleasures, spiritual contemplation, and spending time with family and friends free from the obligations of work and rank.

***

Another post on Medieval Christmas, including a fourteenth-century recipe for the precursors of our mince pies, is available here.

View more of ‘The Golf Book’, one of the books used to illustrate this post, here. Technically it’s not ‘medieval’ as it was produced in the sixteenth century, but it gives a nice sense of the Christmas season.

For more images from Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Bodley 264, a medieval copy of The Romance of Alexander, click here.