On Friday I posted about contemporary depictions of Elizabeth Woodville. Today, I’d like to share four other documents relating to her.

The first, British Library MS Royal 14 E iii, is a fourteenth-century book of Arthurian Romances. Originally owned by Charles V and VI of France, the book passed to John, duke of Bedford (the first husband of Elizabeth’s mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg) in the early fifteenth century.

It was later owned by Sir Richard Roos of Gedney and his niece, Eleanor Haute, who inscribed ‘Thys boke ys myne dame Alyanor Haute’ on folio 162. However, it’s another name, ‘E. Wydevyll’, inscribed just above Eleanor’s that makes this manuscript so interesting. It may refer to Elizabeth’s brother, Edward Woodville, but it could equally be a reference to Elizabeth, perhaps even her autograph, from a time before she was queen.

- ‘E. Wydevyll’ and Eleanor Haute’s inscription in British Library MS Royal 14 E iii, fol. 162r.

- The first folio of the book also contains the names of two of Elizabeth’s daughters, ‘Elysbathe the kyngys dowter and Cecyl the kyngys dowter’, providing a clearer connection between the book, the royal household, and the queen.

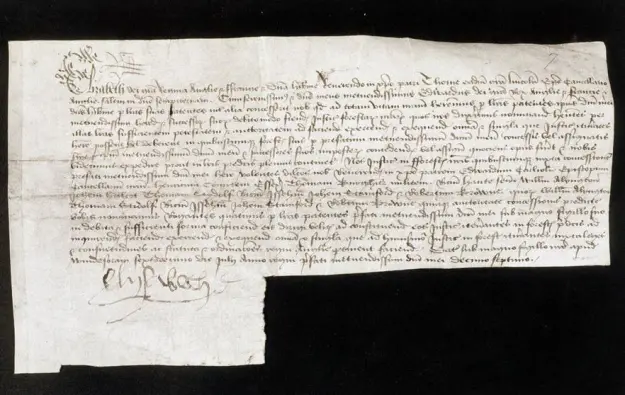

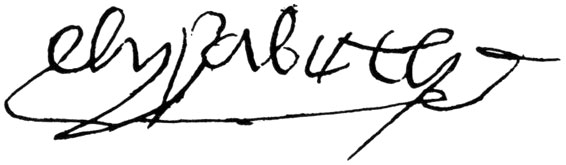

Another document that leaves us in no doubt what Elizabeth’s royal signature looked like is a letter from the queen to the Bishop of Lincoln dated 1477. A professional scribe copied the actual letter, but ‘Elysabeth’ signs it at the bottom.

- Letter from ‘Elysabeth’ to the Bishop of Lincoln, 1477. Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. A. 289, f. 7r.

- This autograph is almost identical to the one she signs in 1491, confirming receipt of her annuity from Henry VII.

-

The following year, on 10 April 1492, Elizabeth made her will at Bermondsey Abbey, where she was residing. She had nothing of consequence to bequeath to her surviving children, so she left her blessings and instructions for her ‘smale stufe and goodes’ to be used to settle any debts ‘as farre as they will extende’:

‘In Dei nomine, Amen. The xth daie of Aprill, the yere of our Lord Gode MCCCCLXXXXII. I Elisabeth, by the grace of God Quene of England, late wif to the most victoroiuse Prince of blessed memorie, Edward the Fourth, being of hole mynde, seying the worlde so traunsitorie, and no creature certayne whanne they shall departe frome hence, havyng Almyghty Gode fressh in mynde, in whome is all mercy and grace, bequeath my sowle into his handes, beseechyng him, of the same mercy, to accept it graciously, and oure blessed Lady Quene of comforte, and all the holy company of hevyn, to be good meanes for me. Item, I bequeith my body to be buried with the bodie of my Lord at Windessore, according to the will of my saide Lorde and myne, without pompes entreing or costlie expensis donne thereabought. Item, where I have no wordely goodes to do the Quene’s Grace, my derest doughter, a pleaser with, nether to reward any of my children, according to my hart and mynde, I besech Almyghty Gode to blisse here Grace, with all her noble issue, and with as good hart and mynde as is to me possible, I geve her Grace my blessing, and all the forsaide my children. Item, I will that suche smale stufe and goodes that I have be disposed truly in the contentacion of my dettes and for the helth of my sowle, as farre as they will extende. Item, yf any of my bloode wille any of my saide stufe or goodes to me perteyning, I will that they have the prefermente before any other. And of this my present testament I make and ordeyne myne Executores, that is to sey, John Ingilby, Priour of the Chartourhouse of Shene, William Sutton and Thomas Brente, Doctors. And I besech my said derest doughter, the Queue’s grace, and my sone Thomas, Marques Dorsett, to putte there good willes and help for the performans of this my testamente. In witnesse wherof, to this my present testament I have sett my seale, these witnesses, John Abbot of the monastry of Sainte Saviour of Bermondefley, and Benedictus Cun, Doctor of Fysyk. Yeven the day and yere abovesaid’ [from J. Nichols, A Collection of all the Wills, now known to be extant, of the Kings and Queens of England, pp. 350-51].

Elizabeth died on 8 June 1492. Four days later, she was buried beside Edward IV at St George’s Chapel, Windsor.

You must be logged in to post a comment.