Though Christmas was very different in the Middle Ages, many of the pastimes and activities that we associate with it would have been familiar to medieval people. Feasting, playing games, singing, drinking around a fire, decorating the house with evergreens, and giving gifts, are just some of the traditions enjoyed in the medieval festive season.

The activities depicted at King Arthur’s Christmas court in the famous fourteenth-century romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight provide a nice insight into the festivities at a late medieval court:

The king was at Camelot at Christmas time, with many a handsome lord, the best of knights, all the noble brotherhood of the Round Table, duly assembled, with revels of fitting splendour and carefree pleasures. There they held tourney on many occasions; these noble knights jousted most gallantly, then rode back to the court to make merry. For there the celebrations went on continuously for fully fifteen days, with all the feasting and merrymaking which could be devised; such sounds of mirth and merriment, glorious to hear, a pleasant uproar by day, dancing at night, nothing but the greatest happiness in halls and chambers among lords and ladies, to their perfect contentment […] While New Year was so young that it had just newly arrived, on the day itself the company was served with redoubled splendour at table. When the king had come with his knights into the hall, the singing of Mass in the chapel having drawn to an end, a loud hubbub was raised there by clerics and others, Christmas was celebrated anew, ‘Noel’ called out again and again. And then nobles came forward to offer good-luck tokens, called aloud ‘New Year gifts’ profffered them in their hands. [translation from W. R. J. Baron’s Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Manchester University Press]

As this passage illustrates, Christmas in the Middle Ages was a lengthy affair. Preparations and celebrations started well before 25 December, and continued long after. Though peasants returned to work after Epiphany (the twelfth day of Christmas or 6 January), the higher ranks might celebrate for longer, like Arthur’s hosting of tournaments and feasting over fifteen days. Truly extravagant festivities might even extend until Candlemas on 2 February.

A festive feast representing January in the Très Riches Heures of John, duke of Berry (fifteenth century)

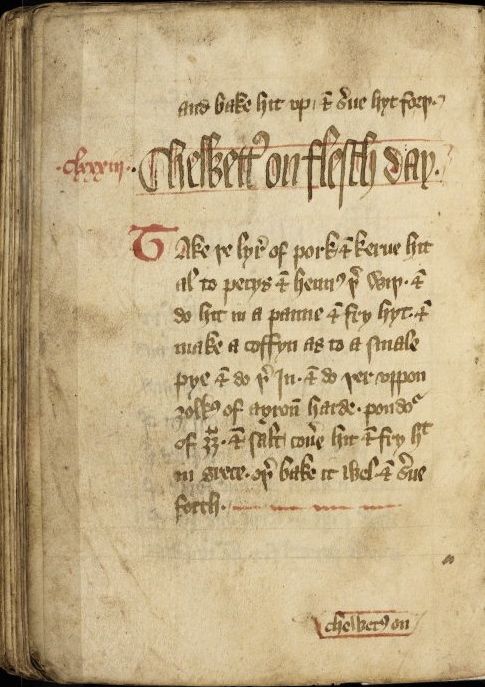

The anonymous Gawain-Poet does not describe the individual dishes eaten at Arthur’s feast, but he does evoke the spectacle of a royal banquet, telling us that each course was brought out to ‘the blaring of trumpets’, ‘kettledrums’, and ‘pipes’, and that the dishes contained ‘the richest foods, fresh meat in plenty […] and various stews’; each couple shared ‘twelve dishes, good beer and bright wine’. Food served at a Christmas feast would include roast meats (especially wild boar), fowl, pies, stews, bread, cheese, puddings, ‘sotelties‘ (elaborate decorative dishes designed for entertainment, often with religious or political significance), and mince pies. Unlike the pies familiar to us, medieval mince pies, or shred pies, were bigger, rectangular shaped pastries (known as ‘cofins’), filled with minced meats like pork, eggs, fruit, spices, and fat. No specific recipes for them survive, but the Forme of Cury, a recipe book compiled c. 1390 by Richard II’s master cooks, contains a recipe for ‘chewettes’, which are similar, smaller versions of the medieval mince pie:

Chewettes on Flesch Day. Take the lyre of pork and kerue hit [carve it] al to pecys and hennes therwith and do hit in a panne and frye hit and make a coffyn [pastry] as to a pye smale and do therin and do theruppon yolkes of ayron [eggs] hard, pouder of gyngur and salt, couere hit and fry hit in grece [grease] other bake hit del and serue forth.

It’s easy to imagine Richard II’s court celebrating Christmas over many days like King Arthur, eating course after course of the dishes described in the Forme of Cury. An account book of 1377 records that twenty-eight oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten at the king’s Christmas feast, and the chronicler John Hardyng, describing the excess of the king’s household in the 1390s, notes that ten thousand people a day attended Richard II’s court and that they were provided with food and drinks by three hundred cooks and servants.

Celebrations in noble and gentry households were much smaller in scale, but nevertheless impressive. A letter from Margaret Paston to her husband John, written on 24 December 1459, includes a list of activities that their neighbour Lady Morley did and did not allow in her household the previous year when she was mourning the loss of her husband:

there were no disguisings [masques], nor harping, nor luting, nor singing, nor no loud pastimes, but playing at the tables [board games], and chess, and cards, such activities she gave her folk leave to play and none other [my translation]

Quieter pursuits, such as board games and cards were clearly suitable for a house in mourning, but louder and more spritely Christmas entertainments, such as singing, playing music and watching masques were not.

So, as you sit down to eat your Christmas dinner, tuck into a mince pie, sing Christmas carols, or play a board game with your family or friends this year, why not share your knowledge of the medieval Christmas and exchange the medieval Christmas greeting recorded by the Gawain-poet too – ‘Noel!’

Pingback: Medieval Christmas | Dr Sarah Peverley