The current controversy over plans to build a tunnel under Stonehenge has made me think about medieval depictions of the site again. Over the years, I’ve come across various descriptions of Stonehenge in medieval chronicles, but I haven’t thought seriously about them since preparing volume 1 of John Hardyng’s Chronicle. This post aims to gather together the earliest accounts and images of the stones.

A view of Stonehenge. Image taken by Sarah Peverley

Written and revised between 1129 and 1154, Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum, or History of the English, lists the stone circle as the second of four marvels in England. Henry’s brief but thought-provoking description conveys the sense of wonder and mystery that medieval people experienced when seeing the stones. Unsurprisingly, the response is the same for many visitors today.

Quatuor autem sunt que mira uidentur in Anglia […] Secundum est apud Stanenges ubi lapides mire magnitudinis in modum portarum eleuati sunt, ita ut porte portis superposite uideantur. Nec potest aliquis excogitare qua arte tanti lapides adeo in altum eleuati sunt uel quare ibi constructi sunt.

There are four wonders which may be seen in England […] The second is at Stonehenge, where stones of remarkable size are raised up like gates, in such a way that gates seem to be placed on top of gates. And no one can work out how the stones were so skilfully lifted up to such a height or why they were erected there.

Translation taken from Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon. Historia Anglorum, ed. and trans. by Diana E. Greenway, p. 23.

In addition to being the earliest medieval reference to the site, Henry’s account has the accolade of being the first to provide the name “Stanenges” or “Stonehenge”. The etymology of “Stanenges” is up for debate, but it derives from either the Old English words for stone and gallows/hang (i.e. hanging stones), because the sarsen trilithons look like medieval gallows, or the Old English words for stone and hinge, because the lintels suspend, or hinge, on two standing stones.

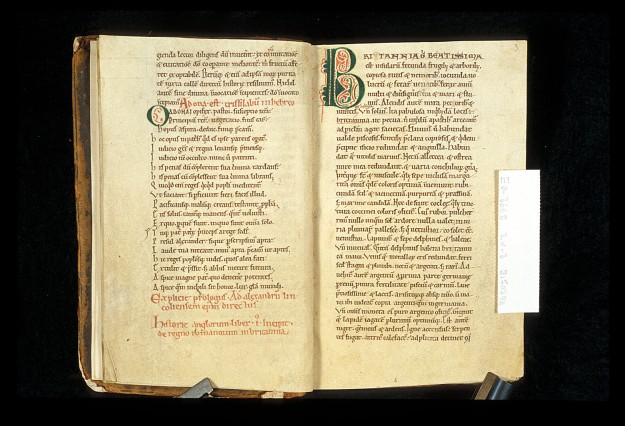

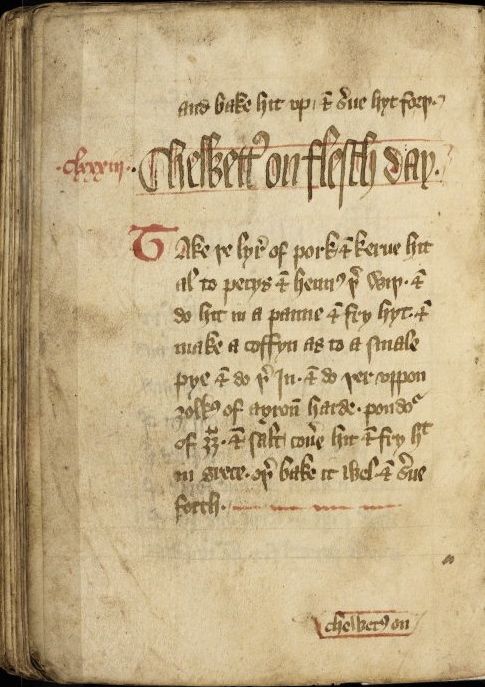

Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum. London, British Library MS Egerton 3668, ff. 2v-3r

At the same time that Henry of Huntingdon was composing the Historia Anglorum, a Welshman named Geoffrey of Monmouth, was writing the Historia Regum Britanniae, or History of the Kings of Britain (c. 1138). Geoffrey’s account of British history became one of the most influential works of the Middle Ages. It also provided a mythic origin for Stonehenge. In his account of the reign of Aurelius Ambrose, an early British king, Geoffrey describes how Aurelius sought a fitting monument to mark the burial site of the British chiefs slaughtered at Amesbury by Hengist, a tricksy Saxon leader. Merlin (of King Arthur fame) informs Aurelius of a structure in Ireland called “The Giant’s Ring” (aka “The Giants’ Dance” or “The Giants’ Carol”), an ancient stone circle with magical healing properties that will stand for all eternity if erected at the burial site. Merlin agrees to bring the stones to England (they are too heavy for normal men to lift!) and departs for Ireland with Aurelius’s brother, Uther Pendragon (King Arthur’s father), and Uther’s men. A battle between Uther and the Irish king ensues, during which the Irish are defeated. Uther’s men build devices to transport the stones, but they only work when Merlin employs his superior knowledge to improve the designs. The stones are taken to Salisbury and erected as a monument to the dead. Later, Aurelius and Uther are buried at The Giant’s Ring.

Here are the relevant extracts for those wishing to read Geoffrey’s account in full (skip ahead if the summary above is enough):

As Aurelius looked upon the place where the dead lay buried, he was moved to great pity and burst out in tears. For a long time he considered many different ideas about how to memorialise this site, for he felt that some kind of monument should grace the soil that covered so many noblemen who had died for their homeland […] Merlin said to him: “If you wish to honour the grave of the men with something that will last forever, send for the Ring of Giants which is in now atop Mount Killaraus in Ireland. This Ring consists of a formation of stones that no man in this age could erect unless he employed great skill and ingenuity. The stones are enormous, and there is no one with strength enough to move them. If they can be placed in a circle here, in the exact formation which they currently hold, they will stand for all eternity.” […] “These stones are magical and possess certain healing powers. The giants brought them long ago from the confines of Africa and set them up in Ireland when they settled that country. They set the Ring up thus in order to be healed of their sickness by bathing amid the stones, for they would wash the stones and then bathe in the water that spilled from them; they were thus cured of their illness. They would even mix herbs in and heal their wounds in that way. There is not a stone among them which does not have some kind of medicinal power.” When the Britons heard Merlin’s words, they agreed to send for the stones and to attack the people of Ireland if they tried to withhold them. At last they chose Uther Pendragon, the brother of the king, along with fifteen thousand armed soldiers to carry out this business. Merlin was chosen so that they could be guided by his wisdom and advice. When the ships were ready, they set sail, and, with prosperous winds, made for Ireland. [Battle ensues and the Britons are victorious] Having achieved this victory, the Britons went up Mount Killaraus and gazed at the ring of stones in gladness and wonder. As they all stood there, Merlin came among them and said: “Use all of your strength, men, and you will soon discover that it is not by sinew but by knowledge that these stones shall be moved.” They then agreed to give in to Merlin’s counsel and, through the use of many clever devices, they attempted to dismantle the Ring. Some of the men set up ropes and cords, and ladders in order to accomplish their goal; but none of these things were able to budge the stones at all. Seeing all of their efforts fall flat, Merlin laughed and then rearranged all of their devices. When he had arranged everything carefully, the stones were removed more easily than can be believed. Merlin then had the stones carried away and loaded onto the ships. [The stones are transported back and celebrations are held…] the stones were set up in a circle around the graves exactly as they had been arranged on Mount Killaraus in Ireland. Merlin thus proved that his craft was indeed better than mere strength.

Extracts taken from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, trans. by Michael A. Faletra (Broadview Press, 2008), pp. 150-53.

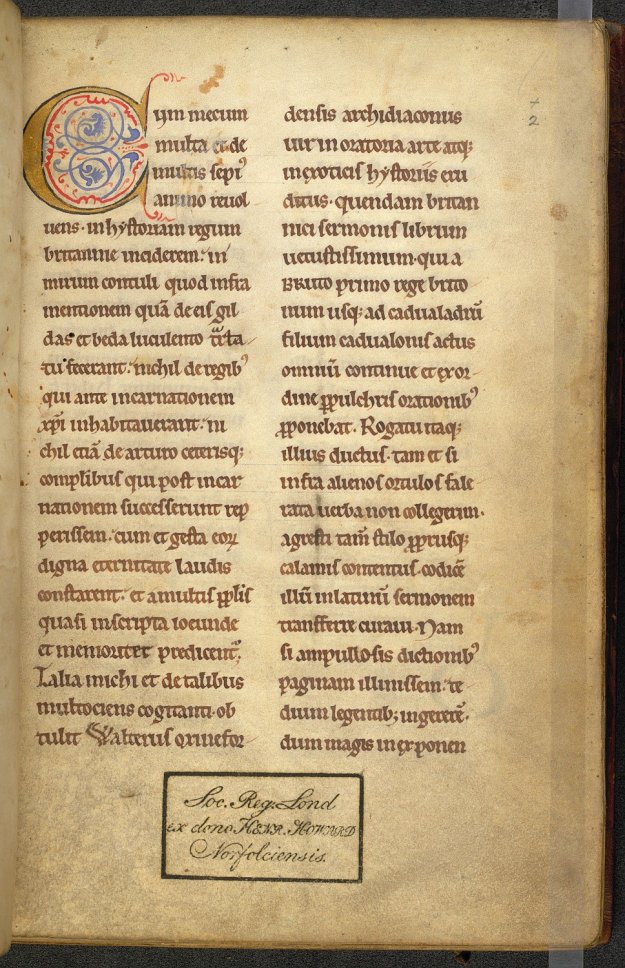

An early copy of Geoffrey’s Historia. London, British Library MS Arundel 10, f. 2r

Geoffrey’s account of Stonehenge was repeated and adapted by chroniclers until the sixteenth century. The first to recycle and embellish it was Wace, who completed his Roman de Brut, a history of Britain, in 1155 and provided three names for the stones:

Bretun les suelent en bretanz

Apeler carole as gaianz,

Stanhenges unt nun en engleis,

Pieres pendues en francis.In the British language the Britons usually call them the Giants’ Dance; in English they are called Stonehenge, and in French, the Hanging Stones.

Wace’s Roman de brut A History of the British: Text and Translation, ed. and trans. by Judith Weiss, pp. 206-07.

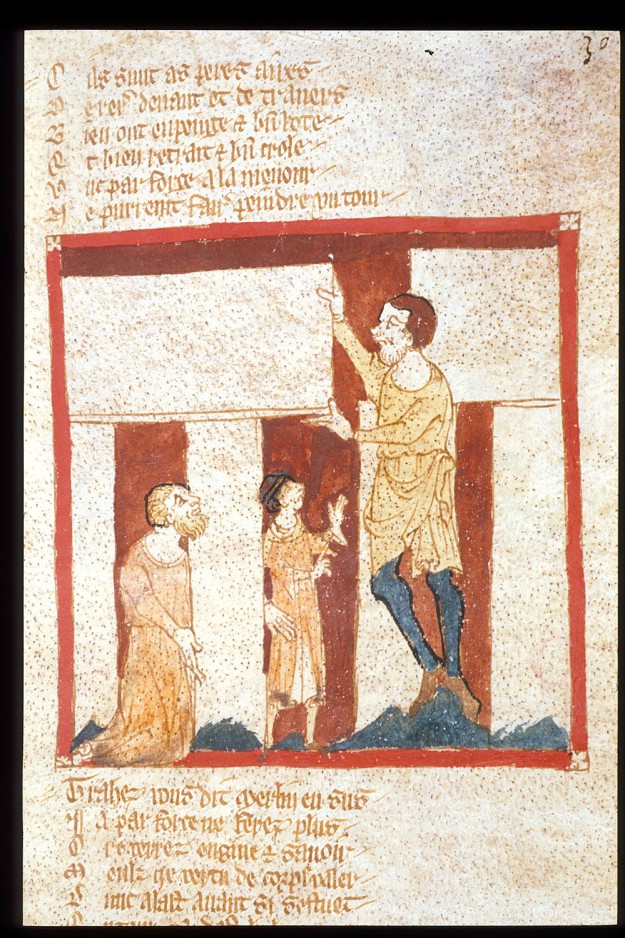

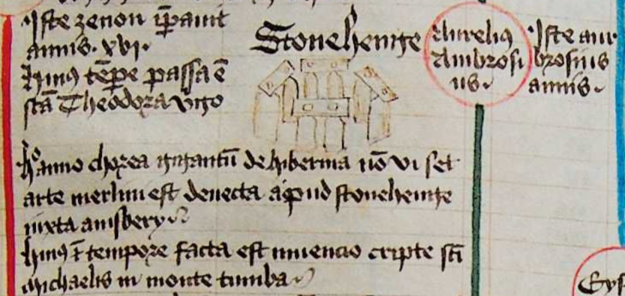

A fourteenth-century manuscript of Wace’s text in the British Library also contains one of the earliest visual depictions of Stonehenge.

Merlin building Stonehenge in London, British Library MS Egerton 3028, f. 30

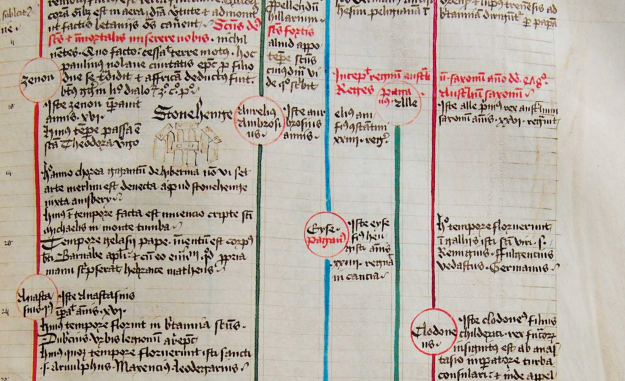

Another early fourteenth-century illustration accompanies a copy of the Scala Mundi, or Ladder of the World, in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College (pictured below). The Scala Mundi is an anonymous diagrammatic chronicle covering world events from creation to the early fourteenth century. Its depiction of Stonehenge occurs, once again, in the reign of Aurelius Ambrose, next to the statement “Hoc anno chorea gigantum de Hybernia non vi set arte Merlini deuecta apud Stonhenges” [That year the Giants’ Carol of Ireland, not by force but by the art of Merlin, was conveyed to Stonehenge]. The text pictured across the stones reads: “Stonhenges iuxta Ambesbury in Anglia sita” [Stonehenge located near Amesbury in England]. The Scala positions Merlin’s removal of the stones within the broader context of world history by placing it in the same period as Pope Felix III and Emperor Zeno.

Stonehenge in a copy of the Scala Mundi in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 194, f. 57

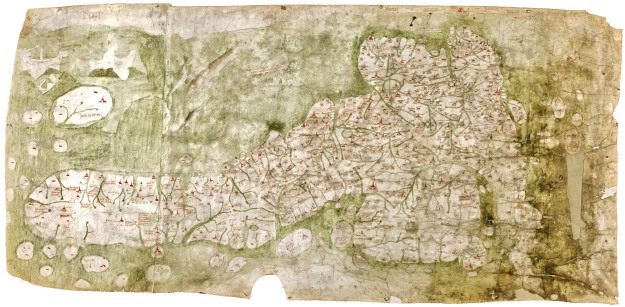

While the images above are recognisable as Stonehenge, the most accurate illustration dates to around 1440 and can be found in another copy of the Scala Mundi (Douai, bibliothèque municipale, MS 803). It was rediscovered by Christian Heck in 2006.

Stonehenge in the Scala Mundi in Douai, bibliothèque municipale, MS 803, f. 55

Close up of Stonehenge in Douai, bibliothèque municipale, MS 803, f. 55

The image shows four trilithons in a circle, with tenons protruding from the lintels. While this configuration and the visibility of the tenons on the lintels is not entirely accurate, the image does appear to have been drawn by someone who knew what the stone circle looked like or had been given a technical description of how the lintels were fixed to the standing stones. But of course, not everyone was as well informed as this illustrator. The mystery and magical allure of Stonehenge and its construction continued into the fifteenth-century when the Northern chronicler John Hardyng commented on the stones:

Whiche now so hight the Stonehengles fulle sure

Bycause thay henge and somwhat bowand ere.

In wondre wyse men mervelle how thay bere .[Which now are called the Stonehenge full sure

Because they hang and are somewhat bowing.

In wonder, wise men marvel how they keep from falling.]John Hardyng. Chronicle, ed. by James Simpson and Sarah Peverley, 3.1915-17.

Writing towards the end of the Middle Ages, Hardyng captures the same sense of wonder that Henry of Huntingdon articulated over three centuries earlier. Today, almost nine hundred years since Henry put ink to parchment to record the name of the stones for posterity, the site still has the power to captivate and confound. Whatever happens regarding the proposed tunnel, we owe it to future generations to protect the integrity of the site and allow it to continue dazzling those who gaze upon it in all its awesome splendour.

For more on the terminology and building of Stonehenge, follow this link.

Lovers of stone might also enjoy Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s wonderful book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman.

You must be logged in to post a comment.