The feast of St Valentine has been associated with love since the Middle Ages. Back then Valentine was one of many saints honoured in the Christian calendar alongside major religious festivals, such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost.

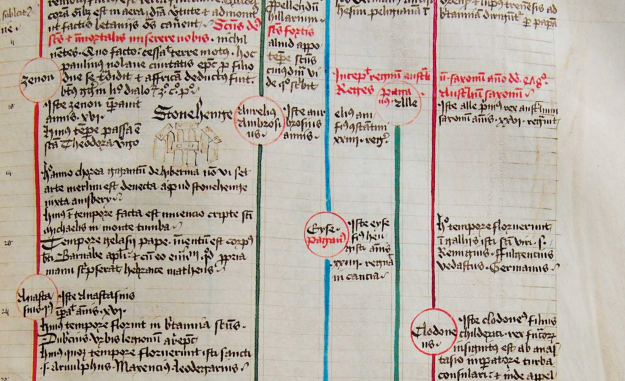

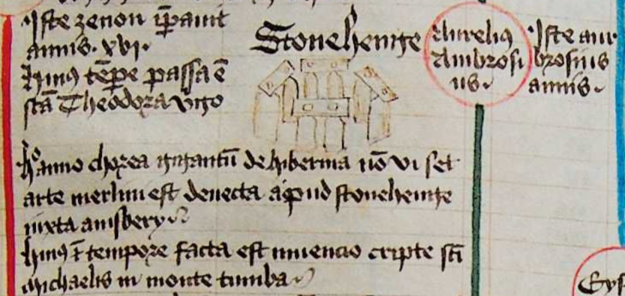

The martyrdom of St Valentine in British Library Royal MS 2 B VII, f. 243.

In medieval times people lived their lives according to the liturgical – or ceremonial – year. But many festivals on the religious calendar also tracked seasonal changes, marking the darkest and lightest times of year, times of planting, harvesting or using up stored food, or signalling the need for people to tighten their belts in periods of traditional shortage.

Little is known about the St Valentine who was martyred on February 14. There are several Valentines in the Catholic martyrology so it’s unclear whether he’s the same saint mentioned by John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer, the first English poets to associate the feast of St Valentine with the mating impulses of birds – which were thought to begin looking for their mates on February 14 (this may have been associated with the sounds of the first songbirds after winter).

But what we do know is that Valentine was not one of the more important saints venerated by medieval people – nor was his feast one of the 40 to 50 festa ferianda, or celebratory festivals, which required people to abstain from work in order to fast and attend mass.

Candlemas

Far from being the main event in February, as today’s British high street retailers would have us believe, St Valentine’s Day was vastly overshadowed by Candlemas on February 2 – or to give it its proper name, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary – which commemorates when Christ’s mother presented her holy child in the temple 40 days after his birth.

Each parishioner participated in a solemn candlelit procession before hearing mass and offering a penny to the church. How people celebrated the rest of this work-free day is not clear – though records of other religious holidays reveal that singing, dancing, playing games, drinking, watching plays and feasting were standard forms of entertainment, despite being frowned upon by church officials. Secular distractions aside, Candlemas had huge popular appeal because it celebrated spiritual renewal through Christ’s light in the darkness of winter. It heralded the end of the cold season and the candle stubs blessed by the priest were believed to ward off evil and protect the bearer from harm for the rest of the year.

Shrovetide

Another festival that has echoes today was Shrovetide, a carnival period before Lent that ran from Septuagesima Sunday until Shrove Tuesday – or as it is popularly known, Pancake Day (Mardi Gras). Shrovetide was similarly well-liked because it provided the opportunity to make merry before the strict rules governing diet, sex and recreation kicked in for the 40 days of Lent, when fasting was obligatory and marriages forbidden.

Second only to the festivities witnessed throughout the 12 days of Christmas, when excessive feasting, music, dancing, and games were the order of the day, Shrovetide, was a time for ordinary people to indulge in food, drink and raucous entertainments, watch plays, and play the popular – but dangerous – game of football.

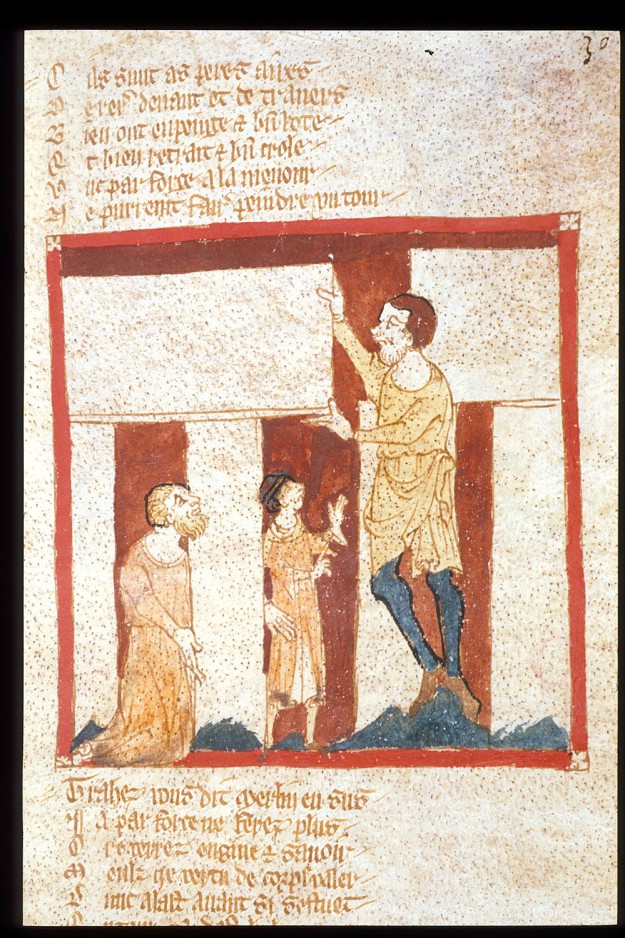

Wood carving of two youths playing ball on a misericord at Gloucester Cathedral. Gloucester Cathedral, CC BY.

Shrovetide also had a practical function. It legitimised the consumption of the last of the food stored over winter before it turned bad, allowing people to prepare mentally and physically for Lent at a time when there was traditionally a shortage of food. The carnival atmosphere also offered a release from the frustrations of winter. Taking its name from the act of shriving – or confessing – sins, Shrovetide captures the very essence of how the medieval calendar absorbed, governed and brought meaning to everyday life.

To everything a season

Of course, there were many other holy days, or holidays, providing occasions for celebration. Christmas, Easter and Pentecost (which celebrates the coming of the Holy Spirit to the disciples after Christ’s ascension) were the principal religious periods – balancing penitential fasting and solemnity with time away from work, merriment and gift giving. And the outdoor revels of early May and summer also played an important role in people’s lives, giving rise to secular rituals such as “Maying” (gathering blossoms and dancing around the Maypole, etc), mummings and various forms of secular and religious plays. Events such as these took full advantage of the spring and summer months, with warmer days providing ample opportunity for large numbers of people to gather together outside and celebrate the natural seasons of rebirth and growth.

The complex seasonal rhythms of the liturgical year remained consistent in England right up until the Reformation, when the observance of saints’ days was abolished and events in the temporal cycle were modified. That some of the Catholic feasts, such as Valentine’s Day, Shrove Tuesday and Halloween (All Hallows Eve) survived the Reformation to remain in our cultural calendar today, is undoubtedly due to the rituals and traditions that secular folk attached to them, an issue that brings us full circle to St Valentine.

Be my Valentine

By the end of the Middle Ages, the meaning of Valentine’s Day had expanded to incorporate human lovers expressing their feelings in hope of attracting or reaffirming a mate. In February 1477, one would-be lover, Margery Brews, sent the oldest-known “Valentine” in the English language to John Paston, referring to him as her “right welbelouyd Voluntyn”. At the time Brews’s parents were negotiating her marriage to Paston, a member of the Norfolk gentry, but he was not satisfied with the size of the dowry offered by her father.

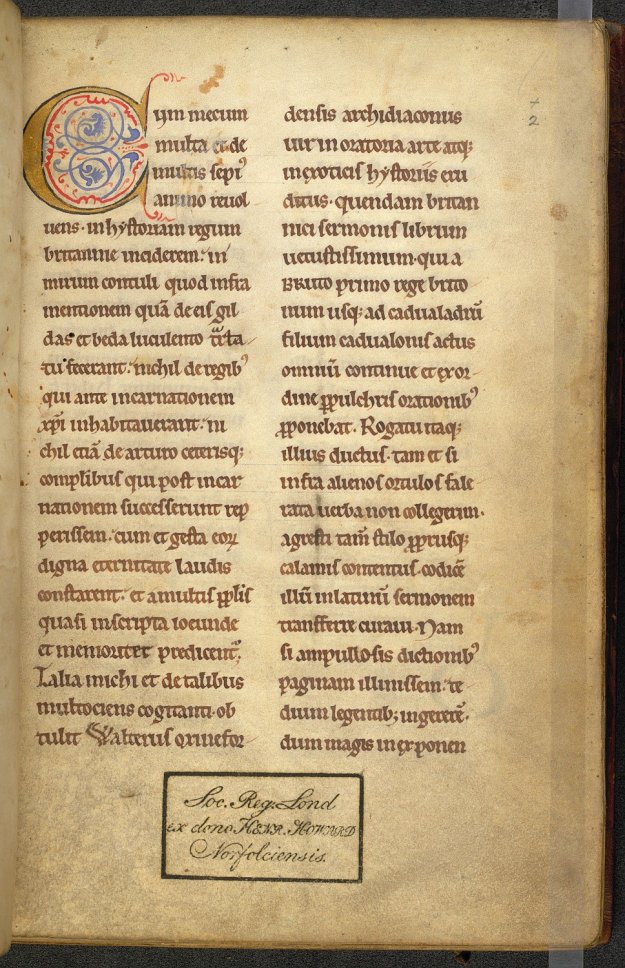

The earliest English Valentine from Margery Brews to John Paston. British Library.

The couple married shortly after, so Margery’s heartfelt letters clearly appealed to her beloved. While we have to wait until the Tudor period to witness the now familiar concept of bestowing material gifts on one’s Valentine, it is Margery’s Valentine that best captures the essence of how the saint’s day transformed from being a lesser-known feast on the medieval liturgical calendar to one of the most important days of the year for hopeful and hopeless romantics, regardless of religion.

Further Links:

A reading of Margery’s letter in Middle English is available on this page.

An earlier blog post on medieval Valentines is available here.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.