Today Scotland votes on whether it should become an independent nation or remain part of the United Kingdom.

The issue of Scottish independence is an old one, dating back to the Middle Ages when various English kings attempted to claim dominion over the land through military and diplomatic campaigns. A Scottish succession crisis in the thirteenth century led to The Wars of Independence, which continued into the late fourteenth-century and were swiftly followed by the Anglo-Scottish Wars. The latter continued, on and off, until 1603 when Scotland and England became united under a single (Scottish!) monarch, James VI of Scotland, also known as James I of England.

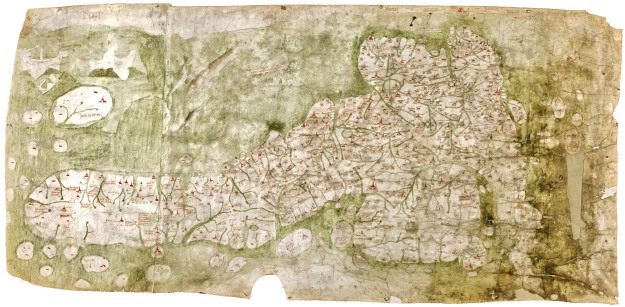

For me, one of the most powerful representations of the historical conflict is the first map to focus solely on Scotland. It was produced during the Anglo-Scottish Wars of the fifteenth century by an English soldier called John Hardyng, who was sent to Scotland as a spy by Henry V. Hardyng’s mission was to obtain documentary evidence of English hegemony and map the country, finding the best routes for an invading army.

For three and a half years Hardyng gathered intelligence for his king, creating detailed maps, plans and documents to support England’s supremacy. Though Henry V never lived to use them, Hardyng later incorporated the materials into his Chronicle of British history and presented them to Henry VI and Edward IV. The map surviving in the earliest copy of Hardyng’s Chronicle, British Library MS Lansdowne 204 (which we can date to 1457), has the accolade of being the earliest independent map of Scotland.

Though it’s compellingly accurate for an early cartographical representation of the realm, and is clearly informed by sound knowledge of Scottish topography, its function is largely symbolic. Accompanied by a detailed itinerary that outlines Hardyng’s invasion plan and offers information on distances and geographical points of interest, the map depicts Scotland as an attractive country, packed with impressive castles, religious houses and walled towns. Its purpose is to show Scotland as a prosperous realm that the English king would benefit from ruling.

Most interesting is the way in which Scotland is cut off from England. The sea surrounds the country on three sides and two rivers seem to sever Scotland from England near the Anglo-Scottish border (shown on the left of the image) .

Although Hardyng’s map is the first to chart Scotland by itself, representations of a physically independent Scotland, or one almost detached from England, are common in earlier maps. Matthew Paris’s famous depictions of Britain in British Library MSS Cotton Claudius D vi and Royal 14 C vii show ‘Scocia’ precariously balanced on top of ‘Anglia’, while the image of the British Isles on the stunning Hereford Mappa Mundi shows Scotland floating alongside its neighbour. Another fifteenth-century map in Harley 3686 separates the countries once again.

Even when Scotland is firmly joined to England, as it is below in British Library MS Harley 1808, medieval artists rarely added the kind of detail found south of the border, giving the country an empty or sparsely populated look.

This is presumably because few medieval people south of the borders had any real contact with, or knowledge of, Scotland to complete the gaps in earlier representations they might have seen. One notable exception is the incredible Gough Map in the Bodleian Library.

Even Hardyng’s map, which is to be treasured for the information it contains, depicts the Scottish highlands as terra incognita: wild, unknown territory best avoided by travellers or invading armies. The earliest version of the map shows this space empty apart from vegetation, much like Harley 1808, but later versions fill the extreme north with the image of a large castle representing ‘The Palais of Pluto, king of Hel, neighbore to Scottz’ [The palace of Pluto, king of Hell, neighbour to Scots].

Blending various traditions that associate the devil with the north and Pluto with wealth, this cartographical feature takes us beyond real geography into the realm of anti-Scottish propaganda; Hardyng draws on the animosity that had grown out of centuries of conflict between the two nations to produce a map that speaks to the political and ideological concerns of his own troubled times.

For more on Anglo-Scottish relations in Hardyng’s Chronicle see my article in The Anglo-Scottish Border and the Shaping of Identity, 1300-1600, ed. by Mark P. Bruce and Katherine H. Terrell.

My short BBC film on Hardyng’s Scottish mission and why he incorporated the maps into his chronicle is here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.