As David Attenborough once observed, ‘Animals were the first thing that human beings drew. Not plants. Not landscapes. Not even themselves. But Animals’ (Amazing Rare Things, p. 9). They are there in the earliest cave paintings, they are there in the cultures of antiquity, and in every subsequent age through to the present day, but no period in history has portrayed them so frequently in its art and literature, or attached such a diverse range of meanings to them, as the Middle Ages.

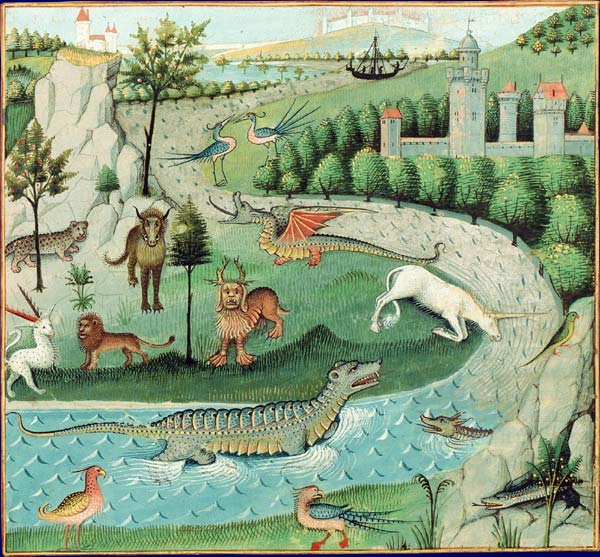

The Book of Nature: Bibliothèque National de France, Français 22971, f. 15v.

The medieval interest in animals extended from the real relationships that man had with them in day to day life – the ox that pulled the plough, the cat that kept the mice away – to the view that they were allegorical pieces in a divine jigsaw that helped define what it meant to be human in a fallen world.

Man was God’s favourite creation, but he had to work hard to redeem his sinful state. For many this meant pondering the wonders of creation and looking at nature for insights into how to live and die well. To the medieval mind, animals had been there from the start, even before Adam was created, so for the wise men and women who studied their appearance, their characteristics, and their activities, these little pockets of wisdom running across the face of the earth, swimming in the depths of the ocean, and soaring in the heavens, were constantly revealing God’s secrets.

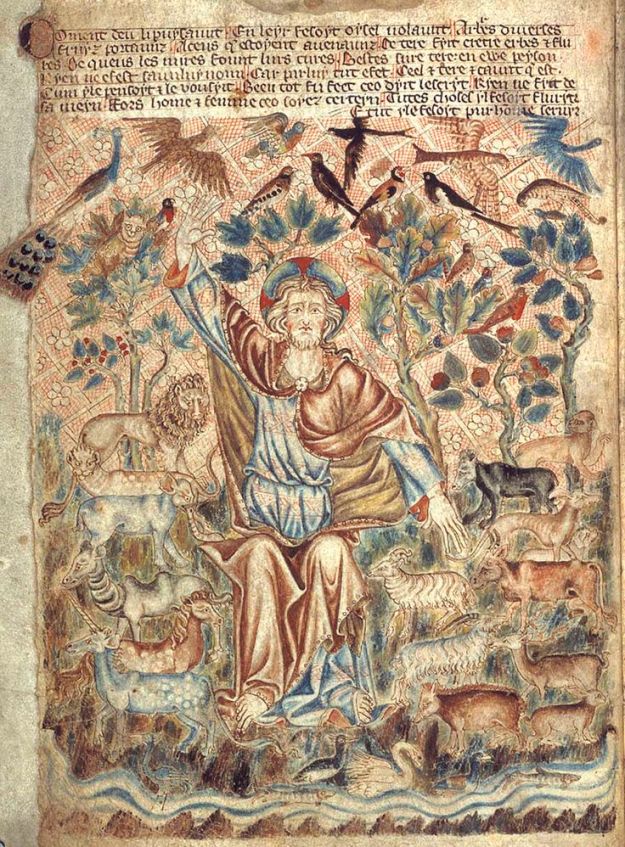

Creation in the Holkham Picture Bible: British Library MS Add. 47682.

Of all the medieval artists and writers that took delight in drawing, writing about, and contemplating the secrets that animals could expose, the authors and illuminators of the Bestiaries, or Books of Beasts, were the most influential. Imbued with Christian symbolism, and blending biblical exegesis, natural science, fantasy, and humour, these encyclopaedic books were packed with descriptions of real and fantastic creatures. Each entry outlined an animal’s supposed appearance and characteristics, then provided a moral interpretation of what the beast represented. In this way, the Bestiaries functioned as schoolbooks, homiletic source material, and devotional aids in monasteries and noble households to help man unlock the secrets of creation.

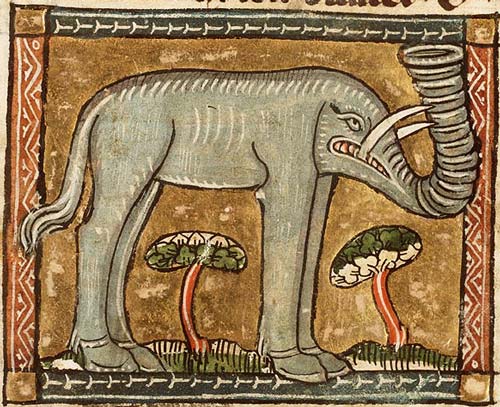

Here’s an example of an entry for the (rather grumpy looking) elephant below.

Grumpy elephant in Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KB, KA 16, f. 54r.

‘Elephants have no knee joints, so if they fall down they cannot get up again. To avoid falling, the elephant leans against a tree while it sleeps. To capture an elephant, a hunter can cut part way through a tree; when the elephant leans against it, the tree breaks and the elephant falls. Unable to rise, the beast cries out, and a large elephant tries to lift it up, but fails… Finally a small elephant comes and succeeds in raising the fallen one… Male elephants are reluctant to mate, so when the female wants children, she and the male travel to the East, near Paradise, where the mandrake grows. The female elephant eats some mandrake, and then gives some to the male; they mate and the female immediately conceives. When it is time to give birth, the female wades into a pool up to her belly and gives birth there. If she gave birth on land, the elephant’s enemy the dragon would devour the baby. To make sure the dragon cannot attack, the male elephant stands guard and tramples the dragon if it approaches the pool. The elephant’s life span is three hundred years. They travel in herds, are afraid of mice, and courteously salute men in whatever way they can.’

Elephant giving birth in Bibliothèque Nationale deFrance MS Lat. 14429, f. 114v.

‘The elephant and its mate provide an allegory of Adam and Eve. When they were still without sin in the Garden of Eden, they did not mate, but when the dragon seduced them and Eve ate the fruit of the tree and gave some to Adam, they were forced to leave Paradise and enter the world, which was like a turbulent lake. She conceived, and ‘gave birth on the waters of guilt.’ The big elephant represents the law, which could not raise up mankind from sin… Christ is the small elephant who succeeded to raising the fallen’. Source of description here.

That’s a lot of hidden meaning in one grumpy elephant!

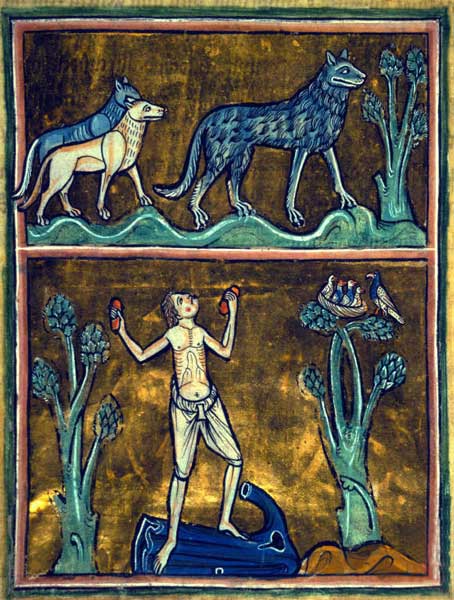

Here’s another for the wolf.

Man and Wolves in British Library Royal MS 12 F xiii, f. 29r.

‘If a wolf sees a man before the man sees the wolf, the man will lose his voice. If the man sees the wolf first, the wolf can no longer be fierce. If a man loses his voice because the wolf saw him first, he should take off all his clothes and bang two rocks together, which will keep the wolf from attacking.

The wolf lives from prey, from the earth, and sometimes from the wind. When the wolf sneaks into a sheep fold, it approaches like a tame dog and is careful to approach from upwind so that the farm dogs do not smell its evil breath… If a wolf is caught in a trap, it will mutilate itself to escape rather than allow itself to be captured.

Wolves have strength in their feet, and anything they trample dies… Their eyes shine in the dark like lamps. At the tip of a wolf’s tail is a tuft of hair that can be used for love potions; if the wolf is about to be captured, it bites off the tuft so that no man can get it… Wolves mate only twelve days in the year. The female gives birth at the beginning of spring, in the month of May, when it first thunders.’

Wolf in Koninklijke Bibliotheek MS KB, KA 16, f. 62r.

‘Like the wolf, the devil always sees mankind as prey and circles the sheepfold of the faithful, that is the Church. As the wolf gives birth when thunder first sounds, so the devil fell from heaven at the first display of his pride. The shining of the wolf’s eyes in the night is like the works of the devil, which seem beautiful to foolish men… Like the man who, because of the wolf has lost his voice, can save himself by removing his clothes and banging two rocks together, so can the man who is lost in sin be saved by stripping off, through baptism, his worldly self and then appealing to the saints, who are called “stones of adamant”.’ Source of description here.

Gorgeously illuminated, the Bestiaries shaped subsequent depictions of animals in literature, sermons, art, tapestries, church architecture, sculpture, furniture, wall paintings, stained glass, and heraldry. Though some of the real bestiary animals bear little resemblance to their living counterparts (many of the artists had never seen the beast they were drawing!), they continue to captivate and delight audiences today.

Take the crocodile for instance. If the beauty tip in the bestiary’s account of the crocodile isn’t enough to make a reader want to delve further into its secrets – to enhance your beauty, smear its excrement (or intestinal contents) on your face and leave it there until sweat washes it off – then perhaps the strange image of its bird-like beak, upside-down head, or lizard-like spikes might do the trick.

Crocodile in Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Lat. 14429, f. 110v.

Crocodile in Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KB, 76 E 4, f. 64r.

Crocodile in Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 764, f. 24.

Crocodile in Museum Meermanno, MMW, 10 B 25, f. 12v.

In Genesis the privilege of naming the animals is reserved for the first man, who is given the task of assigning them identities. This special gift to Adam, his sovereignty over all living creatures, is reflected in the opening pages of the Aberdeen Bestiary, whereby the parallelism between the three images depicting God’s creation of the animals and Adam’s naming of them, underlines the closeness of God to animals, man to animals, and man to God. Together, they form a perfect trinity: divine, human, and animal.

Animals then, were seen as being imbued with certain characteristics because God intended them to provide examples of proper or improper conduct to reinforce his laws. At first, man and animals were created to live in harmony, but after the Fall, new creatures, such as lice and fleas, were believed to have appeared to trouble man and make his life on earth uncomfortable. Animals became something to be feared if they could not be tamed. Two divisions appear with regards to the medieval view of animals, they could either serve man or hurt man: be tame or untame. This is similar to medieval perceptions of the landscape, whereby civilised, controlled spaces were (for the most part) considered to be safer places, while untamed landscapes, wildernesses, forests, and wastelands were perceived to be marginal, liminal places were wild, bad things dwelt. Living in a world full of threat and danger (physical and spiritual) became part of what it meant to be human.

There will inevitably be aspects of our ancestors’ use and love of animals in stories and artwork that we will perhaps never be able to fully understand, but we can be certain that they were used exhaustively in medieval culture to offer another view of the world. In attempting to elucidate aspects of the human condition through animals, the bestiaries express our fears and desires; they speak to man’s insatiable quest for knowledge and comprehension of the world he lives in. Perhaps this is why their influence is still widely felt today in the accepted ‘wisdom’ that lions are the king of beasts, elephants are scared of mice, dogs are loyal, or foxes are cunning, and, more spectacularly, in the creatures that inhabit the imaginary realms of popular series like Game of Thrones or Harry Potter.

Read more about Bestiaries and their animals here.

View the Aberdeen Bestiary here.

View English Bestiaries in The British Library here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.