Last week I was asked to write about my Five Favourite Medieval Hybrids for BBC Radio 3. I’ve been pondering the enduring appeal of mythical beings since I started work on a cultural history of the mermaid, but this feature, and the release of the next instalment of the Harry Potter franchise, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, has got me thinking once again about the powerful place fabulous creatures hold in our imagination and how that maps onto the physical places they are meant to inhabit.

Alexander the Great carried by Griffins in London, British Library Royal MS 20 B xx, f. 76v

Hybrid beings like merfolk, centaurs, and sphinxes, reside in a twilight realm. They have a foothold in two worlds – human and animal – yet belong to neither. They often have sentience and speech, yet visually they epitomise chaos, a convergence of opposites, an impossible binding together of body parts that shouldn’t co-exist.

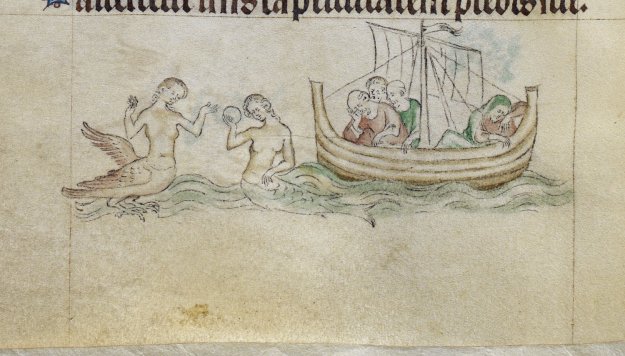

In the Middle Ages, hybrid creatures were frequently used to explain our existence and teach Christians how to live good (or bad) lives. Inherited from the Classical tradition, the sirens and their enchanting song, for example, became an emblem of the devil, ever ready to lure sinners to their destruction with the sweetness of worldly pleasures. The mermaid, on the other hand, might encapsulate vanity. Commonly depicted with a mirror and comb, the accoutrements of pride, she would often appear in manuscripts and churches as a warning against sin. Yet her hybrid body could also be used to represent positive dualities, as the fourteenth-century religious plays known as the Cornish Ordinalia show. Here the mermaid is employed to explain the concept of Christ’s dual nature (part-man, part-god).

Sirens planning an attack on sleeping sailors in ‘The Queen Mary Psalter’, British Library MS Royal 2 B VII, f. 96v

While the bodies of these fantastic creatures could be used to ponder or explain what it meant to live in a fallen world, where corporeal forms could deceive or influence those who gazed upon them, the landscapes inhabited by liminal creatures such as the mermaid, the werewolf, or the centaur, were equally useful for reflecting on the dichotomies of our existence. Typified by duality, the mermaid’s element – the sea and watery regions of the land – could nurture mankind by providing food and connecting cultures, or it could destroy life and civilisation. It was fierce and impenetrable, it was temperamental and unpredictable. It could give and it could take away.

In religious literature and art, the sea often figures as a transitional space: a place of change and transformation for those adrift upon it. Once an individual embarks on a sea voyage, planned or otherwise, they are never the same. A good example is the Middle English poem Patience, which tells the story of Jonah, who must patiently suffer the trails God sends. Another is the breathtaking Anglo-Saxon poem known as “The Seafarer“, which uses the vastness of the winter sea to focus on the isolation of the individual. Even the story of the first founding of Britain, which prefaces the Middle English Prose Brut, begins with a sea voyage. After murdering their husbands to gain independence, 33 Syrian princess are cast adrift on the ocean, only to wash up on the shores of ancient Britain and found a race of giants by copulating with spirits of the air.

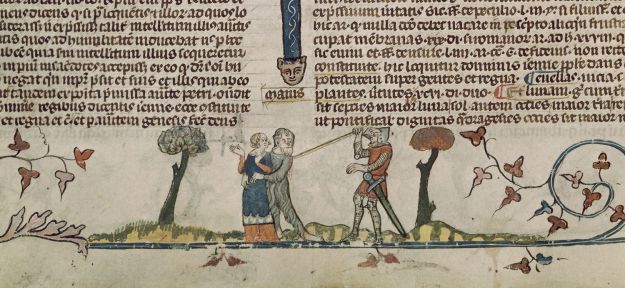

The wilderness or dark forests of Western Europe, were equally dangerous environments for medieval folk. Unsafe, uncharted, and unknown, the medieval imagination populated them with sharp-toothed beasts like werewolves, inscrutable fairies, or wildmen known as wodwoses. The creatures in these spaces are always used to test the humans that venture into them and challenge their way of life. The knights of Arthurian romance, like Sir Gawain, are repeatedly confronted with such trials, as is the eponymous hero of the Middle English poem, Sir Orfeo.

A knight killing a wodwose in London, British Library Royal MS 10 E iv, f. 74v

In thinking about how fantastic creatures and their environments work together to isolate humans and take them beyond the known, the mappable, and the ‘safe’, the literature and art of the Middle Ages can offer us new insights into the medieval mind and how it tried to make sense of the world. In the same way, our own enduring fascination with mythical creatures, such as dragons, unicorns, and griffins, allows us to exercise the power of our own imaginations and ponder what a world filled with fabulous, and often uncontrollable, beasts might mean for the human condition.

The quest to find fantastic creatures in the wild and secret places they inhabit is also the search for ourselves.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like:

Five Fantastic Medieval Beasts and Where to Find Them (BBC Radio 3 website)

The Beauty of the Bestiaries (also featured on Being Human Festival Blog)

You must be logged in to post a comment.