The twenty-third of April is the feast day of Saint George, patron saint of England.

English interest in St George arose in the fourteenth century under Edward III, who created the chivalric ‘Order of the Garter’ in his honour in 1348. The king’s special affinity with the military saint, and his notable success in the Scottish Wars of Independence and the Hundred Years’ War, may have helped to establish St George as the patron saint of England. Banners displaying St George’s arms (a red cross on a white background) were carried into battle at Halidon Hill (1333) for example, and, according to the fourteenth-century chronicler Jean Froissart, the English used the saint’s name as a battle cry before defeating the French at Poitiers (1356).

In the fifteenth century, Henry V’s personal devotion to St George continued to enhance English enthusiasm for the saint. In 1415, English soldiers carried banners depicting St George’s arms into battle against the French at Agincourt and emerged victorious. The saint’s feast day was declared a double holy-day and Archbishop Chicheley ordered that it should be kept as solemnly as Christmas, which meant, among other things, that people didn’t have to work.

By the late fifteenth century, St George was sufficiently aligned with military success, chivalry and national pride, for one chronicler to create a unique mythology for the arms, linking the best kings and knights from Britain’s legendary history with contemporary sovereigns and their chivalric orders.

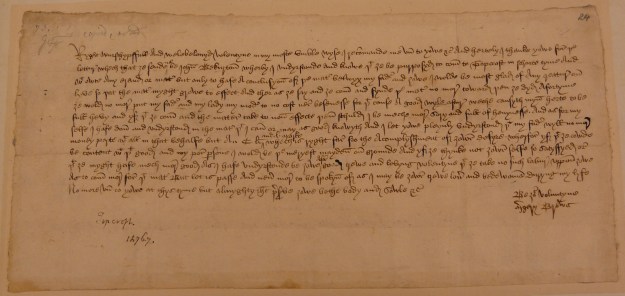

Completed during the civil conflict known as the Wars of the Roses, the two chronicles composed by John Hardyng begin their account of St George’s ‘red cross’ with material adapted from the Vulgate Cycle of Arthurian romance. Hardyng explains that the ‘armes that we Seynt Georges calle’ originated with Joseph of Arimathea. Joseph is said to have given a shield to Evelac, pagan king of Sarras, upon his conversion, which bore a cross of blood in token of the blood spilt at Christ’s Crucifixion. The same device, we are told, was later adopted by the legendary Christian kings, Saint Lucius and Constantine the Great, by the Grail Knight Sir Galahad, who finds Evelac’s shield before achieving the Holy Grail, and by King Arthur, who is presented with a reliquary containing Galahad’s heart in the same way that the Emperor Sigismund presented Henry V with a reliquary containing St George’s heart in 1416.

Hardyng uses the continuity of the arms throughout the ages to connect the monarchs and knights from Britain’s past to the English kings and subjects who have fought under the saint’s banner in his own times. Attributing part of his information to an enigmatic prophet named Melkin associated with Glastonbury Grail lore, Hardyng claims that, long before St George was born, the arms were used to identify the British so that each man would be able to tell his countrymen from his enemies in battle:

These armes were vsed in alle Britayne

For comon signe, eche man to knowe his nacion

Fro his enmyes, whiche nowe we calle certayne

Saint Georges armes, by Mewyus informacion,

Ful long afore Saint George was generate

Were worshipt here of mykel elder date.

Elsewhere, he states that the arms are worshipped throughout the realm, especially by kings, who take them into battle and always emerge victorious. As a veteran of Agincourt, Hardyng doubtless had the victories of Henry V in mind and wanted to suggest that his glorious military success could be repeated again if his king (first Henry VI and later Edward IV) could bring an end to the civil conflicts plaguing contemporary Englishmen and reunite them against a common foreign enemy, such as Scotland or France.

In Hardyng’s history, the arms of St George are a rallying point for all loyal Englishmen, who are encouraged to support their king and emulate the Chronicle’s best proponents of chivalry. It is no coincidence that Hardyng ends the first version of his text with a eulogy for his former patron, Sir Robert Umfraville, a Knight of the Garter under the protection of St George, who is cast as the most courageous, kindest and just knight of his generation.

It is coincidental, but nevertheless fitting, that a century after Hardyng penned the last datable reference in his chronicles (1464), William Shakespeare, the author of the most famous quotation depicting Medieval England’s love affair with St George, is believed to have been born, and would later die, on the saint’s feast day: ‘Cry God for Harry, England and Saint George!’

You must be logged in to post a comment.